I’ll start by trying to stave off the snowball that I expect to gather steam as it barrels downhill in my direction while evolving into an avalanche.

No, this post is not meant to offer a hard & fast rule that lawyers can’t use listservs.

Rather, it’s meant to share guidance from others – much smarter than I – who recently concluded that when using listservs lawyers must be mindful of the duty of confidentiality that they owe to their clients.

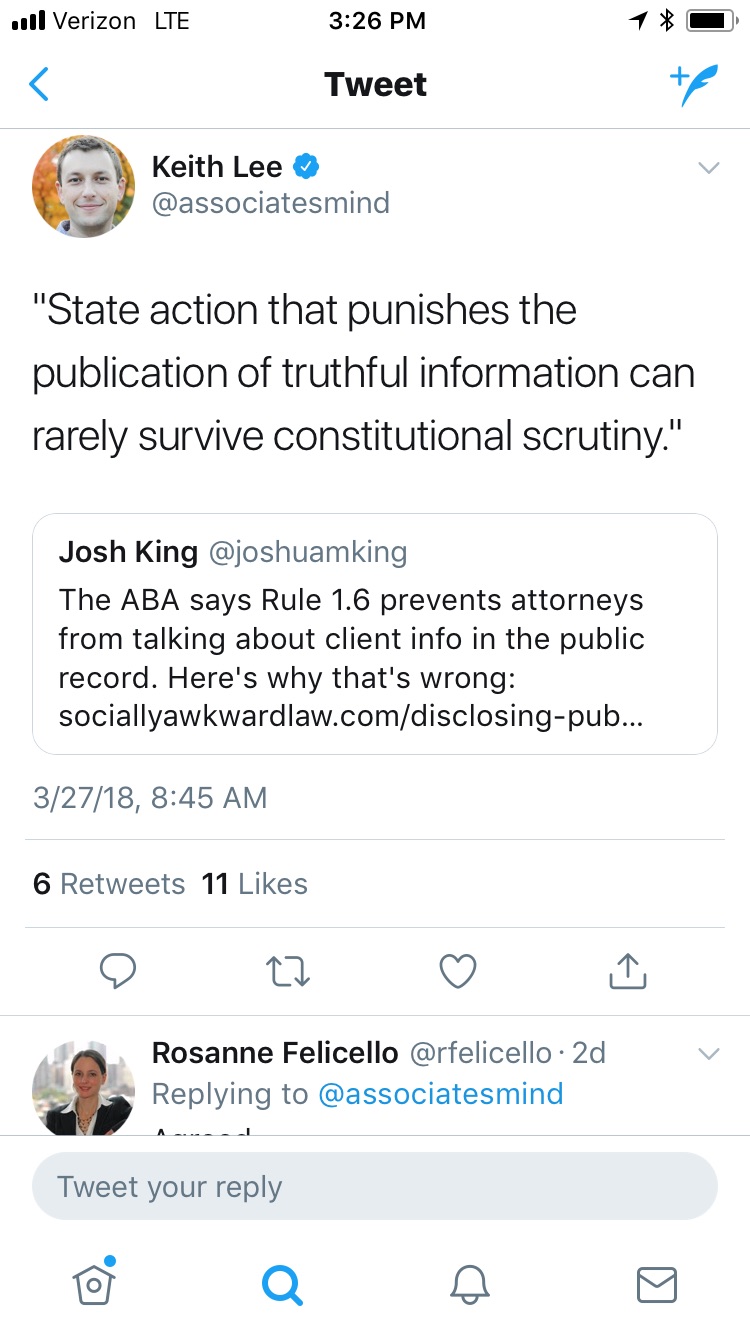

What you do from here is up to you. My suggestion? See the picture.

Two days ago, the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility released Formal Opinion 511: Confidentiality Obligations of Lawyers Posting to Listservs.[1] Here’s the first sentence of the concluding paragraph:

- “Rule 1.6 prohibits a lawyer from posting comments or questions relating to a representation to a listserv, even in hypothetical or abstract form, without the client’s informed consent if there is a reasonable likelihood that the lawyer’s posts will disclose information relating to the representation that would allow a reader then or later to recognize or infer the identity of the lawyer’s client or the situation involved.”

The next sentence clarifies that:

- “A lawyer may, however, participate in listserv discussions such as those related to legal news, recent decisions, or changes in the law, without a client’s consent if the lawyer’s contributions will not disclose information relating to a client representation.”

Now, let’s back up to go over the rule.

The opinion focuses on ABA Model Rule 1.6(a) which states:

- “(a) A lawyer shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client unless the client gives informed consent, the disclosure is impliedly authorized in order to carry out the representation or the disclosure is permitted by paragraph (b).”

Vermont’s Rule 1.6(a) is quite similar:

- “(a) A lawyer shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client unless the client gives informed consent, the disclosure is impliedly authorized in order to carry out the representation, or the disclosure is required by paragraph (b) or permitted by paragraph (c).”

For purposes of this post and the new ABA Formal Opinion, paragraph (b) of the Model Rule and paragraphs (b) and (c) of Vermont’s rule are not relevant. Rather, the focus is on the intersection of:

- A lawyer’s posts to listservs; and,

- Rule 1.6(a)’s prohibition on disclosing information relating to the representation of client unless the client gives informed consent to the disclosure or unless the disclosure is impliedly authorized to carry out the representation.

To avoid a post that is far too long, I’ll restrict myself to sharing’s the opinion’s conclusions and advising lawyers to read the entire opinion for a better understanding of the analysis.

Per the opinion:

- “Lawyers may disclose information relating to the representation with the client’s informed consent.”[2]

- “Lawyers who anticipate using listservs for the benefit of the representation may seek to obtain the client’s informed consent at the outset of the representation, such as by explaining the lawyer’s intention and memorializing the client’s advance consent in the lawyer’s engagement agreement.”[3]

- “In this opinion, the question presented is whether lawyers are impliedly authorized to reveal similar information relating to the representation of a client to a wider group of lawyers by posting an inquiry or comment on a listserv. They are not.”[4]

I understand that the opinion is likely to concern lawyers who use listservs. Indeed, a lawyer who used to do my job (for a long time) in another state expressed concern on social media that the opinion might have a “chilling effect” on lawyers who use listservs.

However, the opinion does not conclude that the use of listservs is unethical. Indeed, the opinion specifically recognizes that “it bears emphasizing that lawyer listservs serve a useful function in educating lawyers without regard to any particular representation.”[5] Nevertheless, “before any post, a lawyer must ensure that the lawyer’s post will not jeopardize compliance with the lawyer’s obligations under Rule 1.6.”[6]

As always, let’s be careful out there.

[1] An ABA Journal feature announcing the opinion’s release is here.

[2] ABA Formal Opinion 511, p. 2.

[3] ABA Formal Opinion 511, fn. 9. Which goes on to state that “the lawyer’s initial explanation must be sufficiently detailed to inform the client of the material risks involved. It may not always be possible to provide sufficient detail until considering an actual post.” Footnote 15 provides even more detail: “When seeking a client’s informed consent to post an inquiry on a listserv, the lawyer must ordinarily explain to the client the risk that the client’s identity as well as relevant details about the matter may be disclosed to others who have no obligation to hold the information in confidence and who may represent other persons with adverse interests. This may also include a discussion of risks that the information may be widely disseminated, such as through social media. A lawyer should also be mindful of any possible risks to the attorney-client privilege if the posting references otherwise privileged communications with the client. Whether informed consent requires further disclosures will depend on specific facts.”

[4] ABA Formal Opinion 511, p. 4. See also, fn. 10: “Comment 5 to Rule 1.6 explains that a lawyer is impliedly authorized to make disclosures ‘when appropriate in carrying out the representation.’ In many situations, by authorizing the lawyer to carry out the representation, or to carry out some aspect of the representation, the client impliedly authorizes the lawyer to disclose information relating to the representation, to the extent helpful to the client, for the purpose of achieving the client’s objectives.”

[5] ABA Formal Opinion 511, p. 6.

[6] ABA Formal Opinion 511, p. 6.

Related Posts

- Hey Lawyers! STFU!

- Can’t keep quiet? Try harder.

- Responding to a client’s negative online criticism? Think twice.

- Ethics tips for lawyers who share office space

- Court upholds order prohibiting Drew Peterson’s former lawyer from disclosing information about Peterson’s ex-wife

- Conflicts of interest involving former clients